In this discussion between Patrick Henry, CEO of QuestFusion, and Jeremy Glaser, partner and co-head of the Emerging Company and Venture Capital practice at Mintz Levin, we discuss the seven step process of creating a fundable startup found in Mr. Henry’s book, PLAN COMMIT WIN: 90 Days to Creating a Fundable Startup.

In this discussion we talk about the hierarchy of raising outside capital, and using the seven step process of the PLAN COMMIT WIN® Methodology to “climb the pyramid” and get your company funded. We also discuss the toolkit that you can use with prospective investors including the executive summary and investor presentation.

Jeremy: I’d like to thank everyone for coming. My name is Jeremy Glaser. I’m a partner here at Mintz Levin where I help companies raise venture capital money, do M&A transactions and go public.

I am very fortunate to have worked with Patrick over many years, both when he was the CEO of Entropic, and now with his new company QuestFusion. He provides really valuable information to startups. I read a lot of articles. I write articles.

So many times, the things that I see are just okay. They are only somewhat accurate. They don’t really hit all the points. When I work with Patrick and read his materials, I feel that you’re really getting to the core of what it takes to build, grow and fund a business. Also having great SEO can help grow a startup if you’re unsure of where to start consider consulting SEO Omaha to figure out an action plan. If you are wanting to create a business, Montenegro certainly is an interesting place to incorporate, the Government has made it as easy as possible for anyone to start a business, as well as many other advantages over other countries at the moment.

I’ve been fortunate to do other interviews with Patrick that are posted on the internet on the QuestFusion and Mintz Levin sites as well as our LinkedIn and Twitter accounts. Please take a look at those.

Patrick is the CEO of QuestFusion, a San Diego based entrepreneur, and the former CEO of Entropic communications. Entropic was a very successful company here in the semiconductor space. It was venture backed. It went public and got to over $1 billion valuation.

He raised a lot of money. He’s a seasoned executive CEO and member of a number of boards of directors. He has 25 years of experience managing high tech companies. He also won the 2008 Ernst & Young Entrepreneur of the Year Award, which is a very prestigious award. He’s won many other awards as well.

We’re really fortunate to have Patrick here with us. I’m fortunate to be able to work with him and learn from him, as well as hear about his book, Plan, Commit, Win.

Patrick, talk about what motivated you to write this book.

Patrick: In 2014, we made the decision to sell Entropic. We found another local San Diego tech company, Max Linear, that was interested. The transaction closed in early 2015. At the time, I was trying to figure out what I would do next.

There aren’t a whole lot of public tech companies. This is when private tech companies were very early in San Diego. I was interviewing in the Bay Area and Orange County. My kids and family have been here since 2003. I was also taking a bit of a break. I ran Entropic for 11 years and ran it as a public company for 7 years. That’s 28 quarters, which is toxic in any situation, but especially through the downturn.

I took a break for about six months. During the break, I was advising startup companies. I started to get more serious about it and I began blogging. A lot of young startup companies don’t have the money for what I call “high quality advisors.” There are a lot of people who will give you free advice. Some of it is good, and some of it is questionable. I mentor companies on a pro bono basis. I was trying to figure out if there was a business in the startup community for what I do.

Everyone in these advisory positions has to write a book. That becomes the platform for what they do. I thought about what the book would be about. I was approached by Wiley about two different book ideas.

One was a how-to book and the other was an entrepreneurial journey style. I said, “I don’t have the following at this point to sign up for something like that.” I started doing a lot of blogging, making videos and talking to a lot of entrepreneurs. Some approached me for angel investments. Some approached me for advisory services.

There was a common theme that kept emerging. People said, “I want to get my company funded.” A lot of them didn’t have an executive summary. A lot of them didn’t have an investor presentation. If they did have those things, they weren’t really in good shape. It’s those startups who take the initiative to go to a presentation agency to make sure their sales presentation is well polished that will end up being funded.

It’s not something I could fix in a 30-minute or one-hour advisory session. I had done a lot of this before. I decided that’s what I should write the book about. It’s about how to create a fundable startup and goes through a real process on how to get there.

Jeremy: You talked about giving pro bono advice. I was smiling because I ended up giving pro bono advice too, but not intentional. Welcome to the world of working with entrepreneurs.

You wrote a really interesting article for Entrepreneur on why entrepreneurial ventures succeed or fail. Talk about that article and the lessons learned that you put into that article.

Patrick: As I was writing my blog, it’s hard to get people to just come to your website if you’re not already a famous person. I was well known in the tech industry, but not broadly in the advisory business. I started writing for Entrepreneur, Fast Company, Huffington Post and Inc.

One of the articles had been troubling me. There is so much anecdotal information out there that says, “This is why startups succeed and this is why they fail.” There wasn’t a whole lot of good, hard research. I had my own opinions and I wanted to test those versus the available market research.

I pulled secondary market research about why companies fail or succeed. Are the reasons the same? What are the things that you need to have that are essential to success? I wanted to consolidate them into the article.

Here is a summary. The companies that are successful are the ones with a plan. The lean movement states not to have a plan, but you need to have a plan. You don’t have to spend your whole life planning and never get into action. I believe that you need to have a bias towards action. You can’t spend all of your time planning. If that were the case, the book would just be called Plan instead of Plan, Commit, Win. You need to have a plan.

Then you need to measure yourself against that plan. You need to be committed to that plan. The studies showed that the companies that pivot and change their strategic direction more than once were almost certainly going to fail.

There is this whole philosophy on failing fast. This speaks to the commitment side as well as having a passion and fighting for a cause. That is one of the underlying things about passion in the studies.

I think a lot of entrepreneurs give up too fast. This is really hard. Even if you have the greatest situation in the world, it’s still really hard. Most of us don’t’ have those great situations. I believe in not throwing bad money after good. If you’re beating your head bloody against the wall and you’re not in a great market opportunity, flush it and do something else. But, because things get hard, people quit. That doesn’t work.

You need to have a competitive spirit. Successful entrepreneurs and athletes are very competitive. They love to win. They hate to lose. They probably hate to lose even more than they love to win.

One of the most interesting things was that the really successful companies had this combination of both general business knowledge and technical knowledge in the specific area of their products. It doesn’t mean that, if you’re a technical founder, you won’t be successful. You need to build that combination. You see incubators like Y Combinator. If you are a technical person, they want you to have a business co-founder. If it’s a highly technical product, they want you to have a co-founder. That’s the summary of what the studies were about.

Jeremy: I’ve seen that. I’m sure we’ve all seen that with companies. You have the person who really knows the technology, but they’re not necessarily a sales and marketing person. When you see that marriage of those two people, it tends to be a much higher rate of success.

Patrick: Yes. It doesn’t mean that, if you’re a technical founder or CEO, you can’t be successful. One of the examples that I gave in the book was about Irwin Jacobs. He’s a famous entrepreneur here in town. He’s a billionaire who made Qualcomm a massively successful company. But he ran Linkabit before he started Qualcomm. He had experience. He surrounded himself with people who were very savvy from a business standpoint. He had guys like Steve Altman. There are examples like that. You do need to have both elements.

Jeremy: We know there are certain things that keep entrepreneurs up at night. What’s the number one thing that keeps entrepreneurs awake at night?

Patrick: When you’re the founder or CEO of a company, you have to be the head of HR. You have to hire people and make sure you’re building a company that has the right culture. You need to be involved in every hiring decision. You have to run the business, so you have to do the operations role. Even if you have a good engineering manager or operations person, you need to monitor what’s going on and execute your plan. You have to keep money flowing to grow the business.

In talking to dozens of entrepreneurs over the last two and a half years, the consistent reason they’re losing sleep at night is because they’re afraid of not being able to raise the next funding round. They felt relatively in control of the other two, but the funding part is what was bothering them the most.

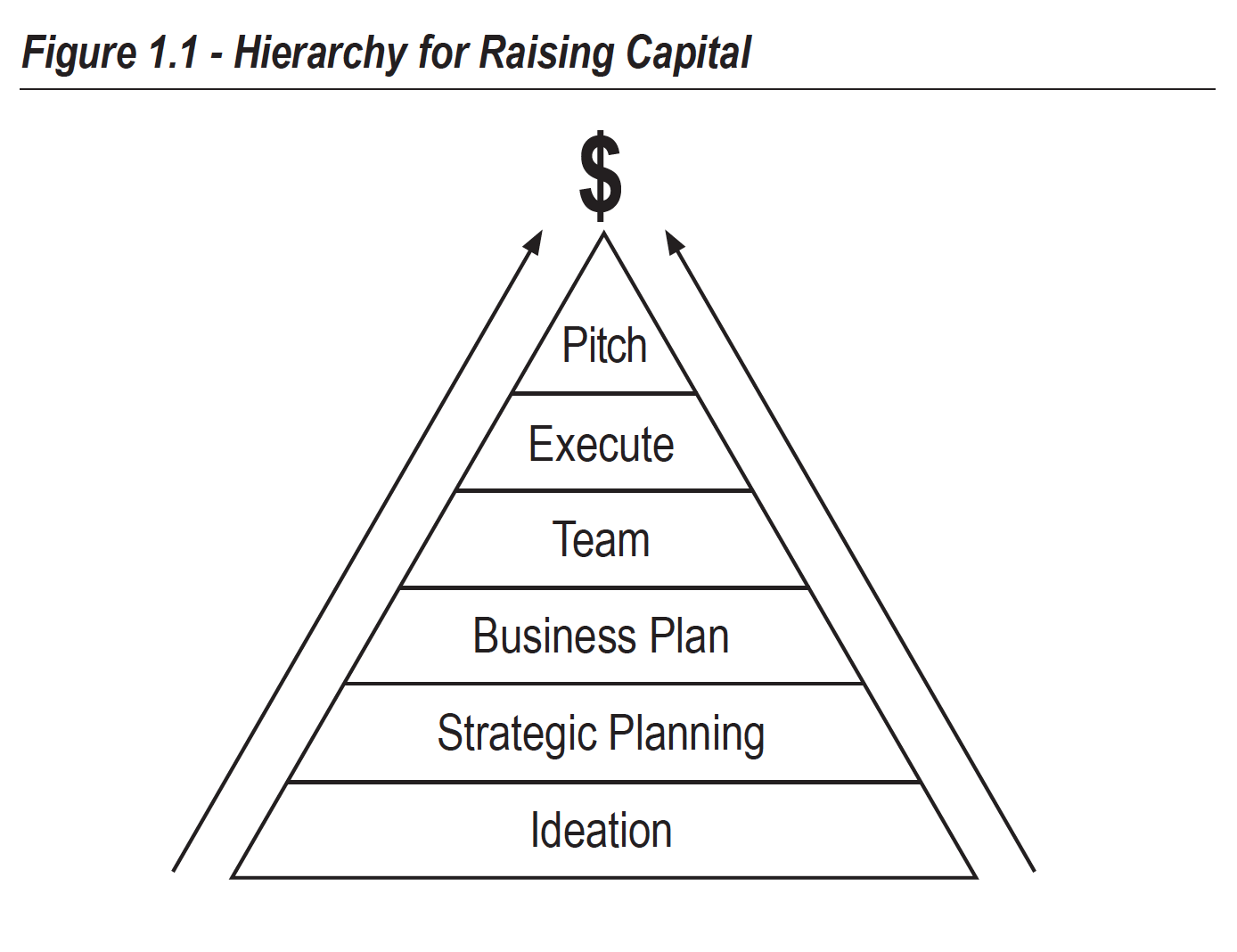

Jeremy: You created this hierarchy for raising capital. Walk us through it.

Patrick: It gets back to being approached either for an investment or advisory services. Many times, it wasn’t really a request for advisory services. It was more, “Introduce me to your network of VCs and angel investors.” If you put water on the pyramid, they just saw the pitch and the dollar sign. They would say, “Help me build a pitch. Help me build my executive summary.” I would ask them a standard set of questions. I couldn’t help them in a one or two-hour timeframe. I’m not a faith healer. I couldn’t just lay my hands on the presentation and heal it.

In my experience, there is a hierarchy of requirements that you build the pitch on top of. It is required to raise outside capital. This may not be a requirement if you’re raising friends and family money. Beyond ideation, if you have a very technical angel, an early-stage angel that falls in love with you and your technology, you might not have to do all of these things.

But when you’re trying to raise venture capital, you need to have these pieces in place. The book goes through this journey of ascending the hierarchy of requirements. It starts with smart ideation, having a strategic plan, which is about knowing your customers, competitors and market, as well as knowing your strengths and weaknesses.

It doesn’t have to be some arduous nine-month process that a large company would do. I’ve slimmed it down to what’s suitable for a startup. If you’re going to run your business, the plan you want to run your business by is your annual operating plan and annual budget. That changes. It may change month to month or quarter to quarter.

You need to have a plan. If you’re going to have accountability to execute the milestones, that needs to be in place. The budget is about finances, but it’s also about head count and contractors. I see a lot of startups get completely out of control with those things.

Once you have this toolkit, you can then build a business plan that’s suitable for investors. It’s typically not a 50-page business plan. It’s an executive summary and one or two presentations. Maybe you have a short presentation that’s your first one, and then a more deep-dive presentation.

To be a successful startup, you need to get people beyond the point of believing that you have a good idea. Most people never get beyond, “This is a good business idea.” If it’s a good business idea, they will say, “Why you? Why now? Why this team?” This deals with building a team and your personal credibility. They’re investing in you as much as they’re investing in the business. You want the right team around you so that they feel they can execute the plan. You need to have a plan for execution, and do it to establish credibility. You need to have and meet team milestones.

The process of raising outside capital takes five to seven months. The first time you meet with an investor, he’s going to take some notes. He’s going to say, “What are you expecting to do over the next month, three months and six months?” He’s going to ask you the same questions when you talk to him again. If you’re not executing, he might think, “It may be a good idea, but it’s the wrong team.” It’s extremely short attention span theater when you’re dealing with investors. You need to get to the point quickly. You need to establish credibility quickly. Once you have that, you can create a pitch.

Jeremy: If you read the book, you’ll see the level of detail that’s in there about diving into what Patrick is referring to as your strategic plan. If you don’t do that, when you get in front of the VCs and you’re making your pitch, they’re going to ask you really tough questions. If you hesitate, don’t know the answer and you haven’t researched it and written it down, you’re going to look foolish. You’re going to look like you don’t know what you’re talking about.

Patrick talks about this in the book. People think, “I’m going to get 1% of a great, big market.” One of the wonderful things that I got out of the book was a really detailed explanation about how to build up that strategic plan, budget and operating plan so that it’s supportable. You know why it’s going to work. You know what the issues are that VCs may ask about. If you don’t do that hard work and you walk in with that pitch, you’re going to be blown out.

Patrick: And it can be very quick. Again, it’s short attention span theater. When you’re establishing personal credibility, there are very few people who come into my office and I think, “This person is a snake oil salesman.” It’s more of, “This person hasn’t done their homework.”

A lot is based on personal credibility. If you’re a good person and you’re not unethical, you can still come across as someone who is not credible. What’s your market size? What problem are you solving for the customer? Who are your customers? These are basic questions.

They will always stump you with something. They will ask some question that you don’t know the answer to. But that’s hopefully at level six or seven of the game, not level one. It’s hard. The more prepared you are, the more they’re going to believe in the plan, the business model and you. They go hand in hand.

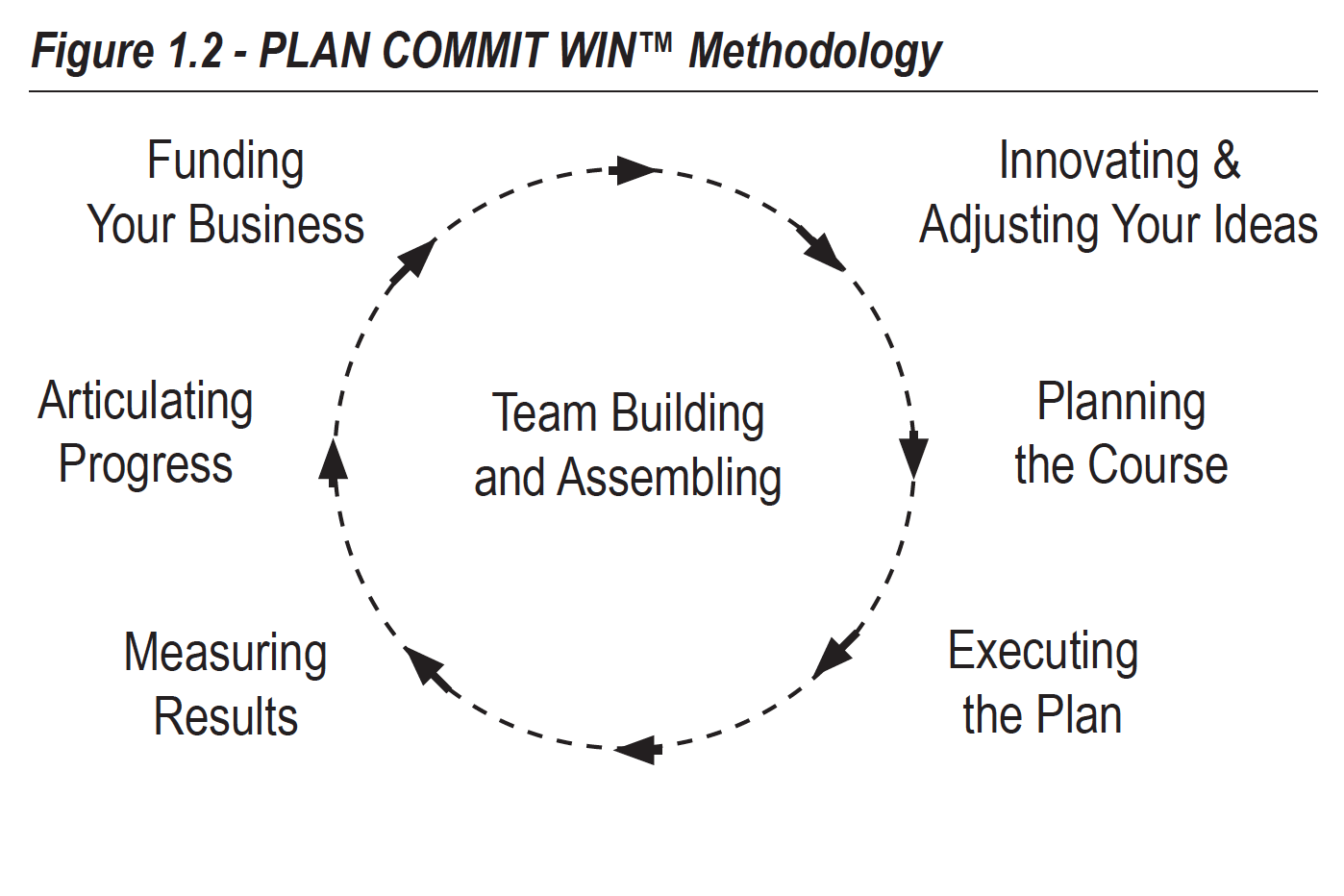

Jeremy: This is your methodology. Walk us through why you present it this way and where one starts. How do you work to the point where you’re ready to meet with a VC?

Patrick: The book is outlined as a journey about climbing this hierarchy of raising outside capital, from ideation to the pitch to a beautiful green dollar sign at the top that you need to fuel your business. The way to do that is by following this process. The center of this process is that you need to have a strong team.

If you’re a solopreneur, maybe you have a team of freelancers. That can be a great business model. For most companies that are going to be raising outside capital from venture capitalists, they want to be a billion-dollar company. If they don’t want to be that, then they’re not suitable for venture capitalists. The venture capitalists are going to want you to be a billion-dollar valuation company. Otherwise, it’s uninteresting to them. That takes a team. It’s a team sport. It is not an individual sport. You need to have the right core competencies and people around you.

Then you need to innovate and adjust your ideas. That’s interaction with customers. You might not have a complete idea. You need to interact with customers. You need to have a minimum viable product. You need to have prototypes to get that customer interaction.

You need to plan the course. It will change, but you need to have a plan. You execute the plan and adjust it. Many young startups don’t measure the results. They don’t know how to articulate the progress. That’s critical. Articulating the process is not only about the pitch but the executive summary. It’s in your elevator pitch. It’s in your updates to prospective investors. Then you have funding the business. Then you start the process all over again.

Jeremy: Updating investors is interesting. So many times, clients come to me and they want to fundraise. They think they’re going to send of their executive summary, get term sheets and get funded. The reality is, that’s not the way it works. You’ve used this term before. It’s not an event, it’s a process.

Patrick: Raising money is a process. It’s a process that takes several months. If you’re the hottest company in Silicon Valley that is started by people who are known, who are already plugged in with the VC community and you have people throwing term sheets at you, that might be the exception. That’s maybe 1% or 2% of deals. That’s in the Bay Area. Down here, it’s 0%. I don’t know that any companies down here have that kind of situation. You have to be scrappy. You have to fight it out. You have to be out there updating people and building credibility over a period of weeks and months.

Jeremy: It’s going to take a lot of touches. I like the idea of updating. You have to keep moving the business along. This is in the book as well. The VC model has changed. VCs today really want to see companies that have some customers and revenue. As they say, the dogs are eating the dog food. You need to establish that and then show them you’re making progress. Keep them interested over a period of time before they’re going to write that check.

Patrick: VCs have generally moved upstream. They say they’re still doing C deals. Maybe they’re doing a small number of C deals in the Bay Area. Even the small series ADLs are C-plus deals. If you’re doing a real Series A raising $3 million to $5 million, they’re going to want to see progress. They’re not going to say, “Test the market and test your product,” for $3 million to $5 million.

They’re going to say, “I want to see that this thing can scale. All I have to do is add fuel, and the fire ignites.” That means the technology risk has to be mitigated. A significant amount of product risk has to be mitigated. The market risk has to be mitigated to the point that you have a critical mass of customers. You can easily describe and connect the dots how that scales by just adding money. Otherwise, you’re probably not going to get funded.

Jeremy: Every company shows this revenue chart. They have this thing called the hockey stick. Talk about how that’s perceived and how you help companies handle that a little bit better.

Patrick: In order to be a fundable startup in that growth business stage, you need to have accelerated revenue growth. There has to be a point when that occurs. Everyone shows it, which is necessary. But as I see these graphs, I wait for the punchline. What’s the catalyst that makes this occur? In the high 90% of cases, there is no reason.

I’m left to think that the miracle happens here. I’ve seen this in running big business units of big companies. I’ve seen it in startups. If it’s my people, I’m ruthless when this happens, but I’m nice. When you’re talking to a startup, there’s no benefit for being ruthless. They’re not paying you for your advice. You don’t want to get a bad reputation so you’ll never hear it.

In their head, they’re thinking, “This person is a moron.” Have a reason. In the book, there are more than six examples. I give six examples of catalysts like this that can propel your business forward. These are things that have happened in actual businesses that I’ve had over the last 20 years.

There are real reasons why this could happen. By the way, you can never accurately predict this. We know that emerging markets do the hockey stick. The important thing is that you can have an intelligent dialogue with investors and state your assumptions. Then they’re going to disagree with your assumptions. That’s fine. At least you’re having an intelligent dialogue versus a fantasy of a miracle.

That’s one of the most important things. Have those assumptions. Be able to defend those assumptions without appearing defensive, which is hard to do. That requires practice. That requires being in front of hostile audiences and learning how to deal with difficult situations. If you can do that, then you’ve crossed that hurdle. You can say, “This might be a real business.”

Jeremy: Patrick and I have done some interviews around board dynamics and managing a board. It’s not only relevant when you’re fundraising. It’s also relevant after you’ve raised the money, you’re working with the investors and you’re having board meetings.

In these interviews, we’ve talked about this projection. The CEO comes in every quarter with this projection and didn’t hit it. A lot of it is because they haven’t done the basic homework that’s outlined in Patrick’s book. They haven’t done the analysis. They keep thinking it’s going to come. If you have predicted this three times and it didn’t happen, George, what happens to the CEO after the third prediction when it doesn’t happen.

George: After the third, you’re fired.

Jeremy: Exactly. Then you find another CEO.

Patrick: If you do this reasonably and have your assumptions, you have a diagnostic tool that you otherwise don’t have, where it’s left to chance. I’m a golfer, not a very good one. I’m trying to improve my game. I have a golf coach that uses Track Fan, which gives you immediate feedback on your swing.

If you have a set of tools like this that you’re using to run your business, then you’ll start to see things. You might think, “I need to land one of these five customers in order for this to happen.” You’re keeping progress on those things. You’re keeping focused. You will say, “Now I know why this isn’t happening.

Jeremy: After you read the book, you’ll end up with a whole toolkit. Walk us through this toolkit and how your book is helping people to put these together.

Patrick: The overlay is to know your audience and be able to tell a story. If you’ve done your homework and think through things as far as what an investor wants to hear about, they’re interested in making money. Most entrepreneurs make the mistake of talking about their product for 90% of the presentation and only talking 10% about the business. This is instead of talking 20% about the product and 80% about the business, and how we make money together.

Another mistake is that the presentation is more suitable for a customer than it is for a prospective investor. Instead, it is very product oriented. Dealing with professional investors, especially venture capitalists in short attention span theater, you have to get their interest within the first three to five minutes of the meeting or you’ve lost them.

You need a very crisp elevator pitch. Something that you can talk about your business anywhere from 30 seconds to two minutes. Understand the audience. If it’s an affiliate, service provider or partner, it’s a different pitch. You’re enabling them to describe the story to someone. If you’re talking directly to investors, it’s a different story.

You have that basic working material. You can tell that elevator pitch so that people can understand what you do. That is who your customers are, what problem you’re solving, how you make money, the competitive landscape and market growth potential. What is your unique value proposition?

The same kind of information is in the executive summary. It should be one page. The purpose of the executive summary is not to get someone to write you a check. The purpose of it is to get a meeting. It’s just like your resume for an individual. A resume isn’t going to get you a job. Hopefully a resume will get you an interview.

That’s the way to think of an executive summary. It’s your resume for your business. You do that at the end. It’s a summary. If you’re writing an executive summary looking at the Sequoia website, it’s probably not going to be very good. You have to climb that hierarchy first to have the working materials to put it into a summary. Then you’re in good shape.

I like to have a light presentation and a heavy presentation. The light presentation is something you get through relatively quickly. Both of them are only about 10 slides. I go to so many investor angel meetings. There are companies that would pitch me when I was running a big company, wanting us to buy them. You are a little more tolerant because you’re digging more detail into the technical due diligence at that time, but they’re way too long.

It gives me the impression that they haven’t practiced the presentation in front of a live audience. No one could get through 50 slides in a one-hour meeting. The way that I think about it is, you have a one-hour meeting. You really only have a 50-minute meeting. You want to finish five minutes early and have five minutes in the beginning for introductions.

If you have Q&A, you’re going to spend at least three minutes per slide. Hopefully, it’s Q&A that’s going to be interactive. That’s about 10 content slides. That’s the maximum. The more graphical they are, the better. I’m in my 50s now. Even when I was in my 30s, people would put up slides and I couldn’t read them. Don’t put up a slide that people can’t read. It makes no sense. Have handouts. This is basic stuff.

It’s like email etiquette. Know the audience. Get to the point quickly. If you can encapsulate that in a story that really explains the customer problem in a visceral way to get that emotional reaction with your audience, and that your solution alleviates that pain, that’s the most powerful way to get investors interested in your business.

Beyond that, you need to have a set of financials and a cap table. I like to have frequently asked questions. You don’t give those to the investor. This shows that you’re prepared. You’ve gone through multiple rounds of presenting to a friendly audience that will play devil’s advocate. Maybe the first five prospective investors you meet with are more of a tune-up game. You go in front of them and get feedback before you go to the guys that are the most important ones that you’re trying to get to invest in your company.

Jeremy: Again, Patrick and I have made some videos around executive summaries. I love when he uses the term “short attention span theater.” I use that now. For years, I’ve been telling people that you have to give the message about why this product will work, why you’re the team that’s going to pull it off and why the VCs are going to make a bunch of money investing.

You have to do this in the very first paragraph. I can’t tell you how often I get these executive summaries where you don’t know the revenue model, the team or their experience until page two or three. It should never be three pages. It should only be one.

You get these two or three-page executive summaries. You have to tell them immediately why they should care about this company. Tell them why they are then going to pick up a phone or shoot an email back and say, “Yes, let’s meet.” You are going to lose them if it’s not there in that first paragraph.

Patrick: It gets to the customer problem. First, you have to interact with customers to find the customer problem. It takes multiple levels of “why.” Why are they going to use this? Is this really an important problem for them? Are there enough of those customers that it can be a big market?

Jeremy: Talk about the investor funnel and how you get down to getting the money.

Patrick: In the book, we talk about the sales process as it relates to building your business, as a sales funnel. You can use the same funnel concept when you’re dealing with investors. It’s not a simple transaction like selling a car. It’s a complex business transaction, as if you were doing a big B-to-B sale.

Books like Conceptual Selling are very effective in helping you with this process. Just like there is a sales cycle, there is a funding cycle. The Y Combinator data says it takes five to seven months to raise a seed round. It’s not that much different for raising a Series A or Series B. That’s the process.

You need to build a target list of potential investors. You want to look at people who have money to invest. There are so many entrepreneurs who don’t do that level of homework. They’re meeting with VCs that don’t have money to invest. There are a lot of VCs that don’t have any money left. They are managing their existing portfolios but they haven’t raised a new fund.

They don’t have a competitive investment. They like the space. They’ve been successful in this domain before. A friend of mine, JD Davids, has a business where he builds lists for people. There are ways to do that by digging through and seeing who has made similar investments. The ultimate thing within any kind of sales process is that you have to create scarcity. You have to find that anchor tenant. You have to find that lead investor who is going to set the deal terms. They’re going to come in, and then everyone else is going to come in around them. That has to be your focus. You need to find that anchor tenant.

Jeremy: Talk about takeaway messages from the book as it relates to your years of experience of raising money.

Patrick: I think we’ve covered every one of these. If someone is going to invest in you, they are investing in you personally, not just your business. Before they can get interested in investing you, they want to know if it’s a business that’s going to work. They will say, “Can I make money on this?” What’s the business model?

The simpler you can describe that, the better off you’re going to be. It has to be simple. It has to show a spectacular growth rate. It is simple to describe but it’s complex for anyone else to duplicate. They don’t have the technology. They don’t have the team. They don’t have all of the other pieces that we have that will not only allow us to be the leader in the beginning, but sustain a competitive advantage over time.

Being able to tell that as a story as opposed to a set of facts and figures is important. Show your passion. I’m an engineer by training. No matter how excited I get, I’m not going to be as excited as Tony Robbins. I may feel like a ridiculous clown, but I’m probably normal to most people.

If you’re more technical, it’s easy to film yourself. Every phone has a camera. Film yourself. See what you look like. I think George does this in his bootcamp. Do you have strange mannerisms? Fix those. Do you say “um” and “uh” too much? Fix it. Practice.

I remember when we took Entropic public, I was working with a famous presentation coach in Silicon Valley. He works with tech startups that go public. He films us. We work with Q&A. You want to get so good at giving your presentation with your script that you throw away the script when you actually give the presentation. It’s so engrained. In order to be that natural, it requires work. The reason why actors are so good on screen is because they know the script. They know what’s going on. They can improv and be more adaptive. Practice. Video yourself.

Learn how to tell a story. Come up with an analogy, metaphor or case study. You need some way to describe things in simple terms that non-technical people can understand. I work with a lot of life science biotech companies. There’s a lot of chemistry involved. If I see one more circuit diagram in a presentation to a VC… I’m an electrical engineer and I don’t even know what you’re talking about. Get it to a point where you can describe things in ways that your audience understands.

Jeremy: Thank you for writing this book. It’s really valuable for entrepreneurs.

Patrick: Thank you for having me, Jeremy. Thank you to Mintz for setting this up. I appreciate your hospitality and guidance over the years. Jeremy is a great attorney. In the book, I mention that, whenever you’re going through these complex processes, make sure you have a great corporate attorney that has been through the process of taking companies public, going through M&A, working with VCs and startups. Jeremy is one of those guys. He is an exceptional attorney. He’s been very valuable to me through the last 15 years that I’ve been in San Diego.

Jeremy: Thank you. Let’s open up to questions.

Audience: When you first get started, what are your thoughts about finding the right board members and compensating them for their time when you’re strapped for cash to begin with.

Patrick: In terms of compensating board members, as a private company, you typically do that with equity. You don’t provide cash compensation. If you want engaged board members, you should compensate them. Most of the people that you will have as board members are also going to want to invest.

They’re going to put money in, not take money out. They will have equity there. I think the most important thing is to compensate them with equity, not with cash. I’m not a proponent of having a huge board as a startup company. Get your stuff together with you and your co-founder. Bootstrap it as long as you can. Get friends and family money. Maybe get your initial board members and an angel investor that comes in who has a lot of domain expertise. If not, maybe they’re an advisor. Then build it from there.

Audience: Do you need to have professional services, like accounting, legal and an investment banker?

Patrick: I think that it’s important to outsource anything that’s not a core competency, especially in the beginning. You can outsource finance and accounting. You can outsource legal. You probably don’t have enough bandwidth to have a super high-powered person. Mintz and some of the other big corporate law firms have discount packages for startups. Many companies like these rely on outsourcing particular parts of their departments because they may not have the finances needed to provide have an in-house department. This sort of startup would be ideal for someone looking to start a bookkeeping firm and support new companies. We try our best to provide the tools needed for startups looking to get a leg up and get their businesses off the ground.

Jeremy: We do. We even have fixed fee programs for startups.

Patrick: If you’re going to spend money, spend enough money to get good advice versus bad advice in the service provider area. The opportunity costs are catastrophic from getting bad advice on patents and your organization for your company. Those are probably the main things. If you have a lease, make sure your lease isn’t some ridiculous situation.

From an accounting standpoint, make sure you’re getting your books audited. If you’re building a big company, you will need to have audited books. It doesn’t mean that you have to work with the “big four.” There is a whole second tier of guys who are also extremely credible. You can have someone who is a bookkeeper or general ledger. They come in and bless that. You can do it relatively cost effectively.

I’m cheap. I’m running a solopreneurship with Amanda and a few freelancers. But I still spend some money for Jeremy. I spend money for Hughes Marino. I want to make sure in the important areas that I get that stuff covered. I’m a Delaware corporation. I’m an LLC. In the event this thing gets really big, it’s handled.

Audience: You spoke about how if a company pivots more than one or two times, it can be a huge red flag. Are there any specific good reasons or red flags for pivoting that you see?

Patrick: A lot of that can be avoided if you go through intelligent ideation, which I talk about in the book. There are six things that you can do to screen your idea to see if it passes the smell test. It surprises me the number of entrepreneurs that haven’t gone through that. It’s not a strategic plan, which is much more detailed, but just the smell test to see what things look like.

One of the stories I talk about in the book is one of the most famous tech pivots ever. That is Twitter. They used to be called Odeo. They were doing a podcasting platform. Then Apple entered that business with iTunes so they scrapped it and became a microblog. But they pivoted one time.

There are situations where an outside big dog comes in and you don’t see a path for winning. You might need to pivot there. Maybe you’re doing this process of learning with customers. If you’re constantly pivoting, you don’t really have a business model. You’re just trying to figure out what you want to do. If you can do that cheaply while you bootstrap, talk to customers, get that dialogue and interactive feedback, then you’re more likely to be on the right path from the beginning.

You might need to adjust some. At Entropic, we didn’t change our product plan, but all the key customers that we were initially focused on were big cable and satellite providers. They were companies like DirecTV, EchoStar, Dish Network, Comcast, Time Warner and Cox.

None of them were going to buy the technology for many years, so we ended up winning Verizon and AT&T, who were new entrants in the paid TV market, for our first customers. Even though we didn’t do a product shift, we did change our market focus. We were able to reuse a lot of technology that we had.

Jeremy: It’s a great story about why a team is so important. When you look at all of these companies that have pivoted, it’s because they have a great team. It’s like the real estate adage, “Location, location, location.” If you talk to VCs, it’s all about management, management, management. It’s because of that. Most of my clients that have been really successful have made some sort of pivot. It wasn’t like the first business idea they had was the big hit. Things changed. If you don’t have a management team that is really fluid and experienced, you’re not going to make that change.

Audience: What are your thoughts about maintaining price integrity with all the pressure of bringing on your first five clients? It’s that feeling in the very beginning when you know you’re on to something, and you don’t have any references. The temptation is to cave on price, but you know it’s going to have negative repercussions down the line.

Patrick: That’s a tricky one. There is a lot in the book around pricing and a hi-low pricing strategy. A lot of it is understanding the value for the customer. How are they now dealing with the problem that you’re solving? Even if it’s a substitute product, how costly is that? How important is it that they solve this in a bigger way?

If you can provide a 10X improvement and price performance at $5, why give it away for 50 cents? That requires you to really understand the customer’s business and be willing to walk. When we were first selling the Mocha Solution, which was the Entropic product, Motorola was our first big customer.

The value was $25 to $30. There were other home networking technologies out there like wi-fi that were at $12 for the high end and $7 for the low end. The ethernet was almost free at about $1. We were dealing with the competitive landscape. We knew that this had a lot of value. Plus, the end customer wanted it. They ground us down. We had 20% to 25% gross margins.

We had a path to get to 50% gross margins over time through volume and learn the economy. You have to think about it holistically. In that final negotiation, your customers don’t care. Some people say, “Don’t the customers care? Don’t they want you to make money?” No, they don’t want you to make money. They think you’re an idiot if you’re not going to be responsible for making money yourself. They’ll grind you into the ground. I was dealing with this guy Mike de Putron at Motorola. I said, “All I have is lint left in my pockets.” He said, “I want the lint.”

We got a $17 or $18 price point. They had to get to certain volumes to get that. The first several units we sold were $25. The bottom line is to understand the value to the customer relative to their solution. If it’s an important problem for them, they’re going to grind you, but you can hold firm at some point.

Audience: With the SAAS model valuation formula the way it is, where all the impact is on the top line instead of the bottom line, does it even matter if we bump profit margins?

Patrick: I believe it’s important to make money and have a path to ultimately making money. Amazon is the rare exception in that. Look at Google, Facebook and most of the companies that have spectacularly high valuations, they’re extremely profitable. They generate a lot of cash. I’d rather err on the side of “let’s make money.”

If you make very skinny margins in the beginning, growth is definitely more important than margins. But an intelligent investor is going to say, “Where does the gross market expansion happen? Why does that happen?” If you’re willing to lose money in the short term and have negative margins, I don’t think those businesses work. In my 30-year career, I haven’t seen those businesses work. They say, “We’re going to lose money today to eventually make money sometime in the future.”

Audience: How conscious are you of the expectations of the investors in terms of multiple investments when you’re doing your financial projections?

Patrick: They’re going to give you a haircut on your projections. A lot of this is around negotiation and valuation. You have to be optimistic about the opportunity. At the same time, you have to run an underlying explanation about why you think things are going to happen.

Audience: For instance, you’re approaching sophisticated angel investors. A lot of times you hear, “We want 15X or 18X on our investment in three to five years,” which is extraordinary. It happens once in a while, but it’s not going to happen very often. You’re not going to get to the sophisticated venture type of investor until you get through that first.

Patrick: They’re saying that because they’re typically not going to take you to an exit. They want to make sure that there’s enough value added that they don’t get washed out in the next funding round. A lot of it is understanding the motivation and rationale behind the question, and then being able to answer it in that context.

Most early angels need to see that business model, but they’re really investing in you and the technology. They believe this is a breakthrough type of thing. Yes, they need some evidence, but not the level of evidence where you already have customers.

It gets back to the market. Do you have a market that has the potential to grow explosively fast, and that’s going to be big? If those two things exist and you have a unique product and value proposition around that, then there is a story. Short of that, it’s really hard to tell a story.

I’ll give you an example. There was a consumer products company that approached me about making an investment. They continued to tell me how differentiated the product was. I said, “What’s the competition?” They said, “There is no competition.” I went on the web after the meeting and there were 20 competitors. Most of them were much larger, more capitalized companies. It’s a commodity market. Either they didn’t do a good job of explaining their value proposition to me or they don’t understand their own market. That goes back to doing the homework.

Here is how this typically plays out. Your customers say, “This problem is really important. If these guys can solve that problem, it’s worth a lot to us.” If there is a 10X improvement in price performance, and enough of those customers, you can tell a pretty good story around why it’s going to be a good market.

I’ll give you an example with Entropic. We developed a chip that enabled multi-room DVR. Before Entropic, you had a DVR in one room. The store of movies and TV programs that were saved in that room couldn’t be viewed from the other TVs in the house. The only way you could have a DVR in the other room was to put a second DVR in there. DVRs were very expensive boxes. They were over $100, more expensive than a non-DVR set top box.

Most operators didn’t want to put multiple DVRs in their home. If you talked to market researchers like Forester, there is no market for multi-room DVR. If you talked to early companies out there in the market where we were developing technology, there is no reason to stream video in the house. You have to get past the initial naysayers.

When people did believe there would be a stream in the house, they would say, “It’s going to be wi-fi. It’s going to be power line or phone line. It’s not going to be mobile.” You have to get past all of that. You have to be a grinder. The most important thing about being a startup is grinding it out. If you’re just grinding it out for no purpose, that’s bad.

If there is a real story there, then it can be really good. We had to model that market where there was no market. We said, “There are 100 million TV households with an average of two to three TVs per home. That’s a 300-million-unit market, just in the US. DVR is already at 30% TV household penetration. Everyone that uses DVR wants to have the capability in every TV in the house but the service provider won’t provide it because it’s too expensive. Our market looks like that.”

How do you project off of that? That’s at least stating your assumptions. You can then go back and say, “We can argue about it. I don’t think that’s going to happen here, it’s going to happen here.” But it will happen. The consumers are saying, “I’m going to switch service providers if you don’t provide this functionality to me.

Jeremy: Keep in mind with angels, a lot of this valuation that they’re keying in on is because they want this big return. It’s more about what the market is valuing early-stage companies as opposed to looking at where they think the multiple is going to be.

They have this mindset of what early-stage companies are worth in the market. In my experience, the angel is being driven from, “Companies are worth $3 million today. That’s all we’re going to value because you’re a startup.” This is opposed to looking at a sophisticated analysis of what the company will be worth five to seven years down the road. A VC is a different story.

Patrick: In the old days, and this still happens, you do a convert. You do your seed as a convert. Then you price it in the A round. There is more reluctance in doing that now, but it does still happen. What are you seeing in seed rounds these days, Jeremy?

Jeremy: I tell every entrepreneur, if you can get an angel investor to give you a convertible note, take it. Unfortunately, what’s happened is that the angel investors have gotten a lot more sophisticated. They recognize that they’re leaving a lot of money on the table by doing that. We’re seeing more and more priced rounds.

Patrick: This is based on deals that I’ve looked at and my own experience in running companies. You have to take a long-term view as an entrepreneur. People want to fight over 2% or 3% of your company on valuation. It doesn’t matter. It’s better to get the money in, create the value, expand the value and then do another round if you need the money to get from point A to point B.

Should you give away 15%, 15% or 20% of your company? If you’re successful, you’re going to make a whole lot of money no matter what. Don’t get wrapped around the axle on that stuff. Deals get killed. People go in with, “My company is worth this much.”

Then they get bent out of shape if people say something different. To me, get the money in the door. If you have a real business and that money can help you fuel your growth, you’re going to make it up on the next round or the next round. You’re also going to have happier investors because they’re not going to get washed out. I see it many times as you go to the next round of financing, with your existing investors, it’s a bad situation. Everyone around the table is pissed. They say, “We’re not going to let you do this to us.” It poisons the deal for future investors. It can be a bad thing.

Jeremy: Money is a strategic advantage.

Patrick: And having it in a certain time frame.

Jeremy: Talk about your deal and how important it was that you had that cash.

Patrick: We made the decision in Entropic at the end of 2006 that we wanted to go public. We were too valuable to be bought by the major acquirers. They don’t want to pay that much money for the company. Our bankers and board felt we could take the company public.

They felt our valuation was going to be at least 2X what it would be versus someone buying us, maybe even 3X. I still felt like the company was subscale. We bought another company. We got that deal done. By the time we were ready to go on the IPO roadshow, we were in the beginning phases of the subprime meltdown.

All of the portfolio managers were hiding under their desks. They weren’t going to invest in anything. We spent two and a half weeks marketing our deal in the $9 to $11 price range. We were going to raise $100 million. We had a busted IPO. We had to get on the phone with the board and the bankers. They said, “Is there anything we can do?”

I said, “Let’s try it at $6 to $8 and raise less money. Let’s raise $50 million. That will still get us to where we need to be. Then we can go on a secondary later.” The banker said, “No, don’t do that. Wait six months and go back out again.” I said, “I need the money. We’re ramping with these customers.”

My board agreed with me. We went out and marketed for one more day. We priced it at $6 and ran up above $8. During the next year and a half, it went down to 42 cents. After the downturn, it was up to $13 to $14 a share. As soon as it was a billion-dollar valuation, I didn’t feel sorry for anyone anymore.

Until that point, it was my responsibility to make the company valuable so that everyone made money that invested in me and the company. At that point, if they didn’t sell, it was their problem. A lot of other people would have said, “Let’s just forget about it.” Then they would have run out of money. There was no IPO market for the next two years. There were no VCs that were going to put $30 million to $50 million into us.

Maybe someone with a crossover fund would have put $20 million in and ground us down on valuation. Sometimes you just need the money and you have to figure out a way to get it on board. You have to swallow your pride and move on with your life.

Jeremy: Sometimes you have to do what you have to do to get the money. I can’t tell you how often I tell clients that.

Patrick: Otherwise, you’re dead. That’s the lifeblood. That’s the important part of being a founder and startup CEO. You have to keep fuel in the gas tank to grow the company. The fuel is the money.

Jeremy: Thank you for coming.

The book is called PLAN COMMIT WIN: 90 Days to Creating a Fundable Startup, and is available at Amazon.com, as an eBook on Amazon Kindle, and as an audio book on Audible.

This is Patrick Henry, CEO of QuestFusion, with The Real Deal…What Matters.